Since I often get questions regarding our development workflow here at Shopware, this entire post is devoted to giving you a little more insight into our quality assurance (QA) process.

As a software company, we try to cover the whole development process in an agile culture, and since the majority of our teams are using Scrum or Kanban, we try to strictly follow the agile manifesto. However, in an agile environment, it’s sometimes difficult to fluently integrate the quality assurance process.

Before I go into what works well, let me share an attitude that doesn't work at all: "We don't need extra testers. Tell the developers they can take more time developing and testing things by themselves, but they have to stop creating bugs."

I don’t think I need to explain why this statement is completely counterproductive, and I’m glad this viewpoint never found its way to Shopware.

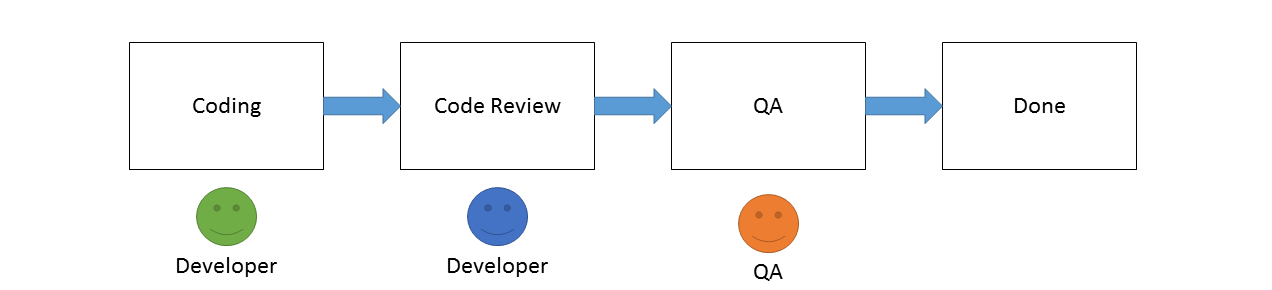

Similar to other IT companies, our development and QA teams worked separately.

You might be familiar with the situation in which several tickets often stuck in the QA phase and the entire development processes seems to stop – this is just one of the problems you face when you have this kind of workflow.

That was until a few months ago when I came across an approach developed and used by Atlassian:

How to deliver quality assurance at speed.

At first I was skeptical because the aforementioned attitude came to my mind. But the more I thought about it, the more it grew on me. After deciding to present the idea to the team, I was surprised to find nearly everyone was on board. So together we decided to give it a try.

Now at this point – and if you haven’t already done so – I highly recommend checking out the video cast from Atlassian.

Dotting

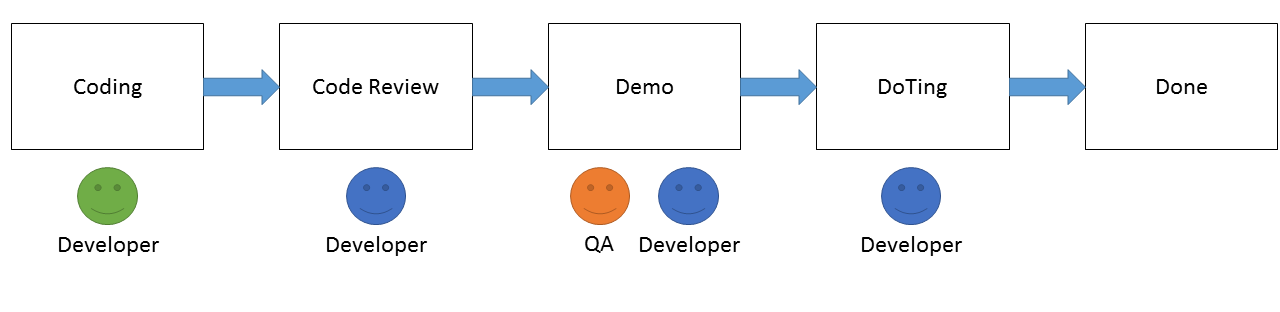

About a week later we started working with the following workflow:

In this scenario, a different developer tests the work of his colleague. After the code review, the tester and developer meet and discuss what the DOT (developer on test) needs to test (demo). An important point of this discussion is to speak about potential risks and testing notes; they should always open questions rather than create a list of click scenarios.

For example: What about the full page cache? What if we use https instead off http?

This allows the developer to learn directly from the experience of the tester. The main goal of this entire approach is to teach the developers how to run tests. After the demo, the DOTs begin the actual testing. Before the software is released, there is always an additional testing phase run by the testers. This is done because of two reasons: first, to have a safety net if the DOTs didn't catch every bug; second, to evaluate the testing quality of the DOTs.

Problems

After a few days we faced a couple of issues, which led us to change the workflow again.

The problems were:

* The developers selected as the DOTs were often the same colleagues, which made the experience unevenly distributed.

* Suddenly the new process was even slower than the process before, because several developers either forgot or postponed their tasks as a DOT. This left the status of many tickets unchanged.

* The author of a ticket didn't feel responsible for the quality, considering it would eventually fall into the hands of a DOT.

Our current workflow

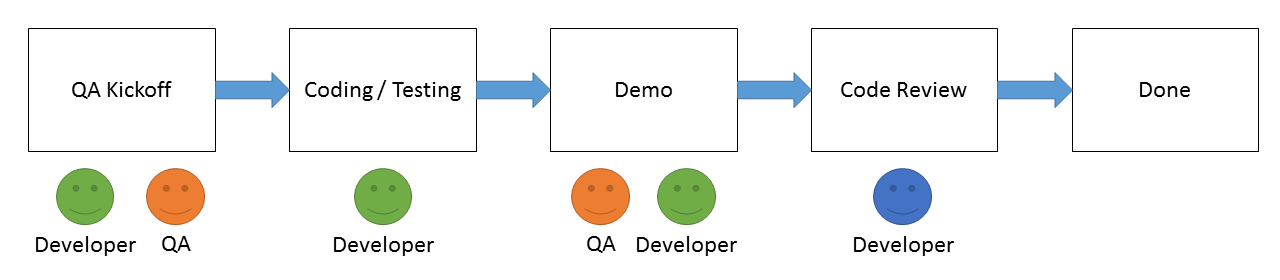

After this experience, we felt brave enough to go on with the last phase explained in the video.

Before a developer starts working on a ticket, he comes together with QA for a kickoff meeting. The point of this meeting is to discuss any risks or important aspects to keep in mind while developing. This is a preventative measure for avoiding bugs before they even exist. After this discussion, the developer starts to code and runs tests at the same time.

After coding/testing, the developer and QA run a normal demo, speak about what has already been tested and try to locate any missing scenarios. The developer then tests the missing scenarios independently so that he knows what to consider in the future.

During the next step, which is a normal code review, an additional developer takes a look at the code. If there is nothing to complain about, the code it merged and the ticket closed. Should the reviewer discover any larger structural problems, the developer is responsible for fixing them and the process goes back to step one with an initial demo meeting.

Before every release, QA performs a release test to make sure everything runs smoothly. Around 5-8% of the tickets in the release still contain a problem of some nature (referred to as “rejection rate”). It is very important to measure this value, because it’s your only indicator for finding out if the ability of your developers to run tests has improved.

In the future, when the testing skills of your developers equal the skills of your QA, you can consider completely removing the safety net.

By the way: when we started with this process, our rejection rate was around 30-40%. It’s safe to say this approach worked extraordinarily well for our team.

Conclusion

One of the best features of this approach is that you no longer have anything blocking this workflow. For this reason, the development process is significantly faster. It also scales perfectly with the number of developers; an ideal advantage for a company that’s quickly expanding.

Because our rejection rate is 5-8% – and we don’t want to take the risk of releasing software with bugs – we have a little way to go before we get rid of this safety net. But we analyze this statistic in every sprint to measure our improvement.

Of course, this workflow isn’t applicable for every team or situation. But for agile environments, it’s especially important to try new things, constantly improve and find the workflow which fits bests for your team.