Computer vision is a very interesting topic in informatics, with huge field of application. It is used in many industries and, with customer PCs becoming cheaper and more powerful, it also becomes more common in that field. Chroma keying, face tracking or even face unlocking are techniques that can be found even on mobile devices.

In this blog entry I will describe how we once used computer vision for our integration tests - and why it didn't work out in our case.

Computer vision

Face recognition with eye detection and face outline.

Image by Kyle McDonald

licensed under CreativeCommons CC BY 2.0

According to Wikipedia computer vision is a field of informatics, that

includes methods for acquiring, processing, analyzing, and understanding images and, in general, high-dimensional data from the real world in order to produce numerical or symbolic information, e.g., in the forms of decisions.

So, generally speaking, it is about processing images or videos in a way that allows for meaningful information to be extracted from it. So whenever there are tasks like "detect me on this image" or "is there a free space in the car parking lot", computer vision (CV) might provide solutions. It is used in industries to check products, in autonomous vehicles or visual surveillance.

Libraries

One of the more popular libraries regarding computer vision is OpenCV. It provides bindings for most platforms (windows, linux, mac, android and iOS) and is available in e.g. python, java, ruby. Also there are libraries on top of OpenCV, trying to make the API more accessible for certain use cases, as e.g. SimpleCV for python. With such tools, it is more convenient to to perform certain tasks, for example to spot cars in a parking lot. So it's quite easy to get good results without any deeper knowledge regarding computer vision and image recognition.

SimpleCV

In the following example I captured the webcam of my PC, detected the position of the eyes and rendered the Shopware logo over them:

#!/usr/bin/env python2

from SimpleCV import Camera, Color, Image, DrawingLayer

import os

import sys

# Helper to get the absolute path of an asset

def get_abs_path(filename):

return os.path.join(os.path.dirname(os.path.realpath(sys.argv[0])), filename)

# Initialize the camera

cam = Camera(1)

# Prepare logo

logo = Image(get_abs_path('logo.png'))

# Loop to continuously get images

while True:

# Get Image from camera

img = cam.getImage()

# Find eyes using a haar feature from http://alereimondo.no-ip.org/OpenCV/34

eyes = img.findHaarFeatures(get_abs_path('eyes.xml'))

if eyes is not None:

for eye in eyes:

# scale the logo for to dimensions of eye

scaledLogo = logo.scale(eye.width(), eye.height());

# render the logo to the eye's position

img.dl().blit(scaledLogo, (eye.x - eye.width() / 2, eye.y - eye.height() / 2))

# Show the image

img.show()

Using the

Using the Camera() call I can access my webcam - if multiples are attached to your PC, you can pass an optional index.

The following endless loop will read the current image from the web cam and process it. In the example above,

a so called haar feature is used, to find my eyes in that image:

img.findHaarFeatures(get_abs_path('eyes.xml')). Haar features are defined using XML and provide recognition for e.g.

head, eyes, mouth or nose.

Afterwards the script scales the previously loaded logo to match the size of the recognized eye. Then the logo is

added to the camera image using the position of the detected eye. The img.show call will show the image in a little window

and update it with each iteration of the while loop. As you can see in the image on the left, it works quite well for live

videos, even though the image processing adds a little delay from the real camera image.

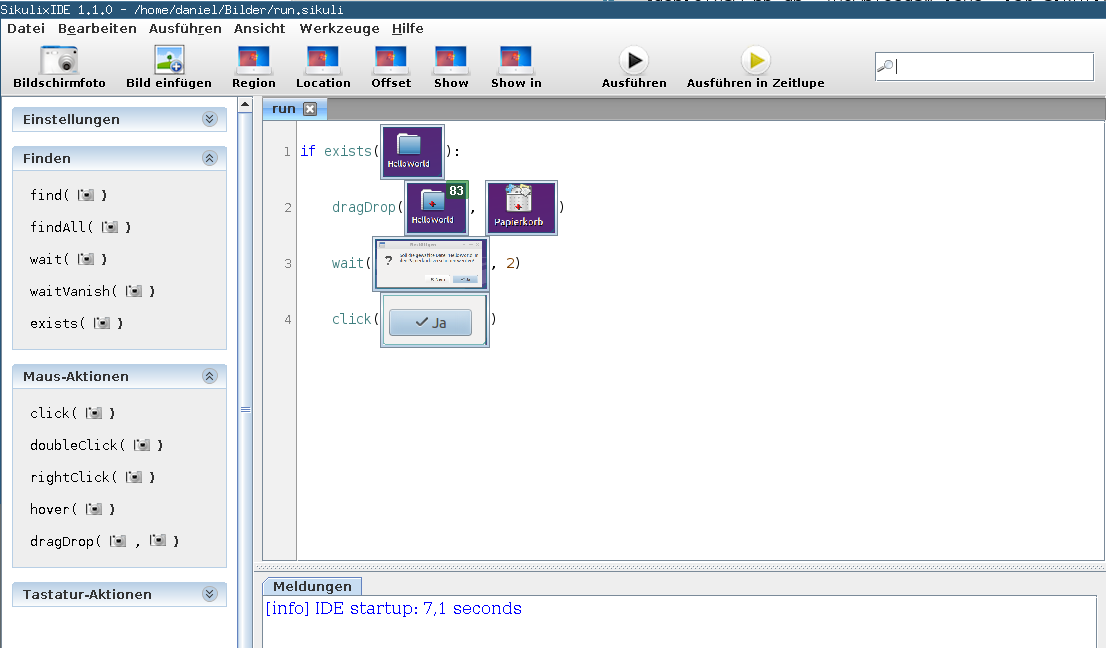

Sikuli

Sikuli is another tool which makes use of computer vision / image recognition. Unlike OpenCV and SimpleCV, it's a whole scripting language based on computer vision.

Sikuli is based on Jython - a Java implementation of Python - and it will allow you to write

scripts in Python syntax. In addition to that, it allows you to query the screen for images. So there are constructs like

Sikuli is another tool which makes use of computer vision / image recognition. Unlike OpenCV and SimpleCV, it's a whole scripting language based on computer vision.

Sikuli is based on Jython - a Java implementation of Python - and it will allow you to write

scripts in Python syntax. In addition to that, it allows you to query the screen for images. So there are constructs like

find (to find the occurrences of a given image) or exists to check if a given image can be found on the screen.

Also there are possibilities to interact with the screen, for example using the click, doubleClick or dragDrop as

well as interactions like type or paste.

The program in the image on top, for example, will search for a directory called "HelloWorld" using image recognition. If a match is found, it will drag the directory to the recycle bin and wait a short time for the confirmation message to appear. When it does, it will confirm the deletion of that directory.

Internally this boils down to a source code like this:

if exists("directory.png"):

dragDrop(Pattern("directory.png").similar(0.83).targetOffset(-7,-11), Pattern("recycle-bin.png").targetOffset(-1,-5))

wait("confirm-boy.png", 2)

click("yes.png")

So this is basically a high level abstraction of the underlying OpenCV library. The result can be seen in this video snippet:

If you run that program you will actually see the mouse moving around and performing actions on the desktop. For that reason, Sikuli is often compared to e.g. AutoHotkey.

Computer vision and testing

The issue is quite common: Using unit tests you can make sure that separate units of your program work as intended. In addition to that, you also want to make sure that all parts combined also work as expected in complex systems (so called "integration tests").

Of course there are wide spread solutions like Selenium, which should be the weapon of choice. But with image processing becoming faster, people also started using it for this kind of testing. For that reason Sikuli or libraries like Xpresser can also be used for this kind of tasks

Why not tools like Mink or Selenium?

For integration tests there are tools like Mink or Selenium, which work great for integration testing your

web application. Shopware also uses these technologies with Mink and Behat.

We also evaluated other technologies, however, as the ExtJS back office with its generated DOM was hard to test using

xpaths like this: //*[@id="gridview-1489"]/table/tbody/tr[4]/td[2]/div/ul/li/span/text(). We couldn't rely on these

xpath being constant over ExtJS updates, and wanted to check if there are other ways of testing this kind of applications.

Furthermore, we wanted to make sure that e.g. the configurator selection is actually visible and usable for the end user - just being in the DOM is not always a real indicator for a usable web application.

These were the main reasons for trying out some alternatives. As said before: It was worth a try - and at the end we found that it was not worth the effort in our case. I will get back to that later.

Our image recognition testing stack

As described above, there are many libraries around that do quite some high level abstractions of OpenCV. For that reason it was reasonable to use such abstractions instead of dealing with the image recognition ourselves.

We decided to build our testing stack using Sikuli, some Python bindings for it and RobotFramework. The RobotFramework is a testing framework which could be compared to Behat, for example. It allows you to describe tests in a human readable syntax.

The following test was taken from out backend testing suite (for the german back office):

Verify that Article module can be opened

Start Browser ${BROWSER}

Login demo demo

Open Menu Entry Artikel Übersicht

Assert Window Is Open Artikelübersicht

Close Window Artikelübersicht

Close Browser

It will start up a browser, do a login with the default credentials, click through the "item" menu to open up the item overview. After the test assured that the window was opened, it closes it again: The test passed.

Internally those human readable commands are dispatched to a Python bridge, which will basically execute code like this:

def openMenuEntry(self, menuName, entryName):

mouseMove("menu/closed/" + menuName + ".png")

if not exists("menu/entry/" + menuName + "/" + entryName + ".png", 5):

self.log.failed("could not find the menu entry named '" + entryName + "' in menu named '" + menuName + "'.")

else:

self.browserRegion.click(getLastMatch())

So the command Open Menu Entry Items Create will be dispatched to a function call to openMenuEntry with the params

menuName and entryName. In here there are Sikuli commands like mouseMove or browserRegion.click() which will

actually perform the mouse movement and the clicks to the menu item. As you can see, the menu item is discovered using an

image that could look like this:  Sikuli would then search the screen for that image and hover it, so that the pop up appears:

Sikuli would then search the screen for that image and hover it, so that the pop up appears:

If the item does not appear (if not exists), it would trigger an error (the build would fail), else it would click on it (click(getLastMatch())).

The same general concept does apply for tasks like Assert Window Is Open or Close Window.

So generally speaking, the concept was not too far from typical Behat / Mink setups - with the difference that the browser automation happened with automated keyboard and mouse inputs and image recognition was used to find certain buttons and elements.

Pros and cons

The general benefit of this solution was the fact that we had a pretty accurate representation of what we wanted to see on the screen, and that the interaction with the web application was technically a real interaction, including moving around the mouse and typing on the keyboard automatically. Furthermore, we didn't have to use e.g. xpaths to somehow emulate what we wanted to see - we could use real images and test for those.

There were massive downsides in our case, however:

First of all, we couldn't emulate the browser - it was a real browser on a virtual desktop, that was automated using Sikuli. This made the tests quite slow and long running. Even more serious was the fact that we become environment dependent: The default CI setup for this solution was running on a certain Ubuntu version with e.g. chrome - a developer with e.g. Arch linux and i3 couldn't run the tests properly, as he might have another screen resolution, font hinting etc. Of course there is always the possibility to increase the threshold of image recognition (thus making the image recognition more tolerant) - but this would also lead the framework to detect e.g. buttons where there weren't any. As a consequence, we had to create the reference images (e.g. the menu item to find) on the same machine where the tests would run - else we couldn't be sure that the images would match properly.

Furthermore, there were massive issues with false positives in the setup: either the framework found too many matches and clicked on the wrong menu item (which lead to errors) or it didn't find the menu item at all - also leading to errors. As a consequence, we didn't detect any serious bugs in our application - but needed to invest a lot of time in fixing and evaluating false positives. Finally, the image based recognition of features (e.g. menu items) was highly dependent on snippets and layout: Simple snippet corrections or style changes automatically required new reference images to be created - thus leading to high effort for maintaining the testing setup.

Summary

The bottom line is that we do not use this solution anymore - the maintenance was to costly and the overall efficiency cannot be compared to our current Mink / Behat setup. All in all, I think there are use cases where image recognition is a perfect tool for testing - in our application, with hundreds of functionalities to be tested and maintained, it didn't work out that well. Even though it did not became a permanent solution for us, I think it shows the possibilities of such techniques and might be very helpful in other testing scenarios. I also really like the combination of a behaviour driven approach with computer vision techniques.

Especially for typical web applications, there are field-tested alternatives in place that should be preferred and that avoid most of the problems I mentioned earlier.